The Baby and the Bathwater:

Water Consciousness in India

By Brook & Gaurav Bhagat

Between the baby and the bathwater, the future looks bleak: with about 20 percent of the global population, India is struggling to meet her water needs with just five percent of the world’s available water. The gap between these numbers is widening, and experts predict that by the year 2020, demand will exceed supply.

Making the issue of water management even more pressing is the fact that many states get as much as 90 percent of their rainfall in the four months of the summer monsoon season, leading to a drought-flood cycle.

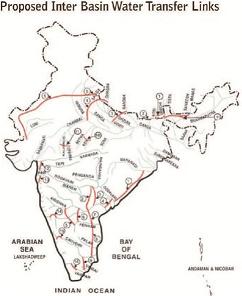

While the main enemy is drought, flooding also kills hundreds and displaces millions of people each year. And, after decades of debate, the government’s main answer is grandiose river linking schemes that would relocate the water to where it is needed-- plans that are yet to reach the drawing board, but extremely expensive, invasive, environmentally risky and possibly impossible.

Since the 1960’s, as the water crisis in India grew more serious, people drilled deeper and deeper into the ground to tap fresh water. The idea was a success at first: the water was used for irrigation for crops needed to feed India's ever-growing population, and farmers began focusing on water-thirsty cash crops. This, along with other “modern" amenities and the shift from rural to urban lifestyles set India on the path to unsustainable water management.

Now, approximately 70 percent of India's irrigation water and 80 percent of its domestic water supplies come from groundwater rather than from surface water, according to the World Bank. In a recent report, the Bank said that India has no proper water management system at all-- her groundwater is disappearing and her river bodies are turning into sewers.

The annual monsoon that once was capable of filling the rivers and recharging the underground aquifers through the soil is losing ground-- or, rather, losing water. In parts of New Delhi, the groundwater level drops by up to 10 meters (33 feet) each year.

Rupert Talbot, a water consultant with the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), described the situation in many areas as irreversible.

"You can go to parts where they are drilling so deep that they are mining fossil water that is 20,000 years old. It will never be recharged (by rains)," he said.

If she continues down this path, Mother India is headed for the official title of being in “water stress" in about 10 years, according to the World Bank. This is indicated by the annual availability of freshwater per head, which is expected at that time to fall below 1,700 cubic meters.

By 2025, with an estimated 1000 cubic meters per head, the situation will be categorized as water scarcity.

Even with numbers like these staring them in the face, there is still “widespread complacency" in government circles about the water situation, according to the World Bank report-- although public promises of safe water and sanitation are abundant, getting there is not quite so easy.

For water, as with every resource, money separates the haves from the have-nots. When the government fails to provide a constant supply of water even in the national capital of New Delhi, those who can afford it find their own ways of getting it. The result is a kind of free market, with no incentive to conserve water.

"What has happened in the last 20 or 30 years is a shift to self-provision. Every farmer sinks a tube well and every house in Delhi has a pump pumping groundwater," said Briscoe, a water issues specialist at the World Bank. "Once that water stops you get into a situation where towns will not be able to function."

Globally, the number of poor people deprived of access to water of the quality and quantity necessary to meet even the most basic levels of health and sanitation. And in situations of scarcity, the poor are of course the first ones to suffer, losing out to those who can afford more powerful machinery for extracting water or those who have more political influence. In India, this means that owners of more expensive pumps and deeper-boring wells are able to continue pumping groundwater, despite rapidly depleting aquifers, leaving the hand pumps and shallow irrigation pumps of the poor high and dry.

Clearly, this is an area where the government should step in--poor people should not be the ones who are disproportionately forced to conserve water, or go without it. If anything, more responsibility for water conservation should fall on the larger, wealthier water users.

But, while it is easy to agree on the magnitude of the problem, it is not so easy to agree on the solution, or even the general direction of the solution. Most people, or at least the most vocal people, seem to favor huge government projects and interventions like the interlinking of rivers-- perhaps many of these people are part of the government themselves. Or perhaps, as a result of urbanization, we have all gotten too used to our resources being someone else’s responsibility-- if there is no heat, or no light, or no water coming from the tap to drink or to flush, someone ought to fix it.

What is needed, in part, is a shift in consciousness: a movement towards self -awareness, the resources we consume, where they come from and where they go to. This is not only true of Earth’s water, but of all our requirements-- food, land, air, energy, everything. Greater self- awareness will lead to greater self-sufficiency-- and, simultaneously, greater consciousness of the interdependence and interconnectedness of all things.

Becoming more aware of and able to meet our own needs can, in a perfect world, make us more aware that everyone needs the same things. We will be better equipped to help each other on the local, personal, practical level-- if you know that your neighbor dug his own compost pit, you will feel more confident (and perhaps even more obligated) to do the same, especially if he knows what you are going through and offers to help you. And, as more people in the neighborhood talk about it and do it, the design and effectiveness of the pits are likely to become better and better.

This is all, however, up in the air. In the real world, one ‘tree-hugger’ might make the effort, and the neighbors will do little more than complain about the dust, or the noise, or whatever else they can think of.

Cartoon: By Cartoosh (Own work) [GFDL, CC-BY-SA-3.0 or FAL], via Wikimedia Commons

This is where bigger groups and ideas come in: the responsibility of government and non-government organizations to organize and mobilize people. Isn’t this what we originally hired them to do? A balance must be struck between personal responsibility and the government (or non-government) promotion, organization, facilitation, and execution of plans and methods to meet our needs.

Sound like a good dream? Now it seems far away, but this kind of communal and personal consciousness of resources actually composes most of human history-- out of necessity. For the 70-80% of the Indian population still living in rural villages, this is still a reality. Everyone in the village knows where the water and food and electricity come from, and where they go to. But the modernization, for lack of a better word, that has swept across the world judges these conditions and values as old-fashioned and time-consuming. Instant gratification, in every element of life, is becoming extreme, and actually eroding the quality of life it claims to improve.

We can speed up the pace of life, but we cannot change human nature. Instant food, water, shelter, and sex leave us without nutrition, love, or peace of mind... and the so-called developed countries are developing insanity, addiction, suicide and war faster than anything else-- not to mention polluting the planet to the brink of disaster.

Photo: User sw77 [CC BY-SA 2.0]

via flicker

In the immortal words of Yoda: Sometimes the way forward is the way back. What is needed is a combination of the fruits of modern technology and development and the self-awareness that brought balance in the past. Now the necessity is different, the risks are different, but the situation is just as urgent; and the first thing we have to change is our consciousness.

One of the first things we might notice if we were more aware is the amount of water we could save by simply catching the rainwater. In the realm of water management in India, this is a movement called rainwater harvesting. One of its biggest champions, Anil Agarwal, is the founder and director of the Centre for Science and Environment and the editor of Down to Earth magazine. On the Editor’s Page of the March 4th, 2007 issue, he wrote:

Until the start of the 20th century most of water use in a highly developed country like India - we must remember that until the British came, it was one of the world's richest, most urbanized and literate nations - was of rainwater and floodwater. Indians knew that almost all the water they got in a year - in a country that is relatively rich in rainfall - was in just 100 hours. The remaining 8,660 hours in a year, the gods gave them nothing. So they built a civilization on these drops of nectar from heaven. Bengal and the Thanjavur delta were one of the most agriculturally prosperous regions in the country and they depended almost entirely on the capture of floodwater for irrigation.

The population, however, is much larger now than it was at the beginning of the 20th century. Combine this with problems like salinity, mercury poisoning and rising levels of other heavy metals in water which have significantly decreased the useable groundwater, and the result is that even if every drop of rainwater was harvested, it would no longer be enough for everyone.

But the emphasis on personal and community responsibility is right on the money, and people are starting to take notice-- like the last State of India Report, which focused on traditional methods of rainwater harvesting.

For more than two decades now, the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE), a New Delhi-based non-governmental organization (NGO), has been promoting the revival of traditional systems of water harvesting, with appropriate adaptation and integration of modern systems. From tanks and talabs to rooftop harvesting systems in the city, rainwater harvesting, with government support, is the most logical and practical way to start trying to solve the water crisis in both domestic and industrial India.

CSE conducts training workshops that are open to everyone-- from engineers, NGO’s and politicians to concerned citizens. And, they have undertaken the awesome project of documenting hundreds of traditional and contemporary Indian rainwater harvesting systems on their website www.rainwaterharvesting.org.

Even a passing glance at these widely varying and often brilliant methods is inspirational-- from delicate bamboo pipeline irrigation to check dams, modern percolation ponds, tankas, kundis, you name it. It is truly an essential and even beautiful collection. By comparison, it makes government plans like “connecting all the rivers" seem short-sighted and incredibly heavy-handed.

India’s population is increasingly becoming the densest on the planet-- but the bureaucracy seems even denser, particularly when it comes to tackling the difficult issue of water management. So many projects and committees and objectives are formed and rarely met, it seems tedious to even think of listing them; but the largest desk animal of them all is the ILR Project.

In the discussion of consciousness, one disturbing aspect of the Interlinking of Rivers project is that, since the government will not have the money to implement the hugely ambitious project, It will go the build-own-operate-transfer route and lease rivers to concessionaires. These operators will own the water resources for several years and will charge users, both urban and rural, for that time period. This goes against India’s tradition of treating water as a community, not private, resource. While money, or the lack of it, already determines the availability and quality of water directly or indirectly for most people, it leaves a strange taste in the mouth-- this is the same country that once respected every river as a goddess.

The interlinking of rivers, while perhaps being a visionary idea, doesn’t seem to have much chance. Whether it is possible or not has not been shown. Even if it is possible, it still seems financially and politically doomed, and most importantly, environmentally risky. It is a hard gamble to claim acceptable losses of any kind of life-- plants, animals, and people will be undoubtedly displaced and in many cases destroyed. Will that water save more lives than it takes? Maybe. It is worth researching, it is worth asking. Every vision is worth trying. But India cannot afford to wait and see if these daydreams can come true or not.

Meanwhile, although rainwater harvesting is the appropriate place to start, this alone is not going to solve all India’s water problems. We have to look for ways to increase the available groundwater supply and decrease the dependence on underground aquifers. We have to find more and more ways to stop wasting, and recycle, the water we have-- in most cases, innovative technology is already there, it is just not cost-effective.

Low-flow toilets, faucets and showers should be mandatory in new construction; composting toilets and many other options exist, but are in most cases too complicated and expensive. The development of these and other new ideas, like natural pollution- and wastewater-cleaning systems (see “Clean the Ganga") should be funded; investment in water and environmental technology is an investment in life. Furthermore, industries and corporations must be held accountable for their actions, taxed and prodded to stop making the situation worse.

This is the government’s place-- to protect the people, and their water, from money-hungry predators. It can also provide incentives for the public to move toward ecologically sound products and practices, as it has already done gracefully on the issue of population control, offering financial and educational advantages to smaller families.

In the end it is a tightrope balancing act, with self-sufficiency and awareness as far as it will go on one hand, and outside organization and direction on the other. While they may seem contradictory, they are not; the solutions are sure to stem from a seat of self-awareness, personal and community responsibility-- not only in water management, but every aspect of life.

Did you like the article? Subscribe here to our New Article Email Alert or RSS feeds.

Sharing is caring! Don't forget to share the love, and keep the conversation going by leaving a comment below:

Advertisement