For the Love of Ganga:

Science, Religion and a Clean Conscience

By Brook & Gaurav Bhagat

"Please consider them an endangered species, these people who still have this faith, this living relationship with the river," pleads Veer Bhadra Mishra, Mahant of the Sankat Mochan Temple of Varanasi, a retired hydraulic engineer and head of the Civil Engineering Department at Banaras Hindu University. "If birds can be saved, if plants can be saved, let this species of people be saved by granting them holy water."

But this priest, coming from the riverside laboratory, knows that the Ganges or Ganga River’s holy water must be cleaned before it can be granted to anyone. For almost 25 years, he has led a political campaign, a scientific development project and a holy crusade to save India’s most sacred river.

When his father died, Mishra was 14 years old. He thus became Mahant of the sect of Hinduism that follows sixteenth-century divine poet Tulsi Das, author of the “Ramayana," one of the most revered Hindu texts. To devotees and to all Hindus-- over a billion people worldwide-- the Ganga is a living mother goddess, a symbol of purity.

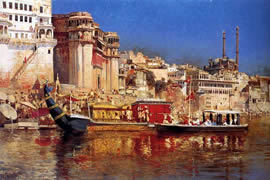

Originally Banaras (Varanasi) was known as Kashi, the holy city from Hindu scriptures. Only here, for 7 Kms., the river turns northward, back towards her source. It is said that the river fell in love with the city and nearly turned back here. The half loop northwards creates the curved bank where the ghats (stairs close to the river) stand today.

Ganga flows some 2,500 km from the Himalayan Mountains to the Bay of Bengal. Her basin is inhabited by nearly 400 million people, making it the most populous river basin in the world. Each sunrise brings 60,000 people, come to bathe and pray at the various ghats of Varanasi. It is believed that if a person’s ashes are placed in the Ganga after cremation, they will go to Nirvana (Heaven).

Therefore, human ashes, and often corpses of those who cannot afford cremation, are emmersed in the river. And although the river is sacred, it is used practically for washing clothes and animals, the disposal of chemical waste from cloth dying and brass making industries, and solid waste like plastic bags, flower garlands etc. Yet the biggest cause of pollution is untreated sewage. 88% of the pollution comes from 27 cities from along the banks of the Ganga.

Dr. Veer Bhadra Mishra is the co-founder of the Sankat Mochan Foundation, a secular, non-governmental organization at Tulsi Ghat in Varanasi dedicated to cleaning and protecting the Ganga, especially from sewage since 1982.

The Indian government initiated the first stage of an unrelated Ganga Action Plan to clean the river in 1984. Three sewage treatment plants and an electric crematorium were built.

Although the major part of the GAP was completed in 1991, testing shows no significant improvement in water quality, not to mention major design flaws, including the backflow of sewage into religious bathing areas, pollution of groundwater throughout the district and backflow of sewage into the streets of the city. The electric crematorium is now used for 80% of cremations, but is plagued by frequent breakdowns which again result in bodies in the water.

The former director of the GAP himself, K.C. Sivaramakrisnan, said, “…In spite of working on this plan for 10-15 years, I do not see the levels of maturity increasing."

Photo: CIA world factbook

Photo: CIA world factbook

The Sankat Mochan Foundation established the Swatcha (clean) Ganga campaign, with funding and support primarily from the United States, Sweden, Britain and Australia. With this outside support Dr. Mishra is able to analyze water quality of the Ganga.

The riverside Swatcha Ganga Research Laboratory monitors water quality daily. Local villages are also suffering from the effects of extreme sewage pollution in their water supply, both from the river and well water. The recent tests indicate faecal coliform levels in the wells of theses villages ranges from 21,000 to 80,000 colonies per 100ml. The safe level for drinking water is zero, for bathing water, less than 150 colonies per 100ml.

Faecal coliform are a bacteria found in the intestinal system of warm-blooded animals; their presence in large numbers indicates pollution by sewage contamination.

The statistics for the ghats of Varanasi are not much better. Here the fecal coliform count at times is up to 3,000 times the level acceptable for human beings. People who are dependent on the river for their water supply often become sick from drinking the water, with hepatitis, typhoid or cholera.

According to WorldWatch Institute in Washington D.C., eight out of ten people in India suffer waterborne stomach disorders at some time in their lives.

The Sankat Mochan Foundation has mobilized volunteers from all over the world. Aside from the laboratory, they have led a large-scale international awareness campaign, utilizing television, radio, print media and the internet. Dr. Mishra has traveled the world learning about the plight of rivers and how activists and scientists have tried to clean them; he hopes that his work for the Ganga will inspire others to clean the waterways they depend on for life.

Among others, he has worked with Thames21, an environmental group in Great Britain. Swatcha Ganga Environmental Education Centre was started by Oz GREEN and the Sankat Mochan Foundation In 1998. It is a direct people to people project which is funded by Australians. They have provided equipment, training and environmental education resources like water testing kits to schools and community groups. The Asia Foundation, based in San Francisco has also provided core funding for SMF’s cleaning project.

Since 2001, campaigners have also cleaned up litter, debris and corpses of humans and animals in the river and along all 77 ghats with their own hands. Numerous sources credit them with improving the situation by one third. SMF has also built tubewells in six neighboring villages, providing clean drinking water to residents who were previously ill from drinking the water of the Ganga.

With the help of William Oswald, an engineering professor at the University of California at Berkeley, Dr. Mishra has developed a plan to clean the Ganga. In his own words, it is “a cost-effective and safe system for cleaning the Varanasi stretch." It is called an advanced integrated wastewater oxidation pond system.

The non-electric wastewater system would store sewage for 45 days in biological oxidation ponds, using bacteria and algae to eliminate pesticides, heavy metals and deadly coliforms, cleansing the entire 7 Km stretch. The system would not only purify water but could be used to irrigate farmland and grow fish. The ponds would be built outside the city limits.

Powered by gravity, the system would save an estimated US$ 55 million annually compared to electrical solutions - which are impractical in Varanasi anyway due to frequent power cuts.

Foundation Members have spoken to the thousands of residents along the river front and in the villages nearby, and more than 6,500 local people have signed a petition demanding the interceptor be built. Over 100,000 people have agreed to help build the dam walls for the oxidation ponds, as an act of religious devotion dedicated to cleaning the river.

Nearly 10,000 local residents have volunteered to build the type of non-electrical wastewater treatment system advocated by the campaign. The Varanasi City Corporation has accepted the plans and the funds are available (about 40 million sterling) but, according to the SMF, the Uttar Pradesh state government is behaving unconstitutionally and blocking Varanasi City Corporation’s plan to clean the Ganga.

In 1994, the 74th amendment to the Indian constitution was adopted, guaranteeing the city’s right to determine and implement environmental policies. While the political standoff continues, the river and its people continue to suffer.

Clean Ganga Day 2004 was held in New Delhi, the political capital of India, on the 27 th of August. The political and environmental issues were discussed by international diplomats and activists.

Addressing participants on Clean Ganga Day, organized by Varanasi's Sankat Mochan Foundation, the U.S. Embassy's Deputy Chief of Mission Robert O. Blake said, "The American people are proud to support your ongoing work to protect this beautiful waterway."

Although Dr. Mishra is an engineer, it is his faith and his heart that keeps him going in this lifelong plight. He says, “We have to clean all the rivers, and then only our heart will be happy. This is what I feel. It cannot be clean just by technology, just by setting up the right kind of infrastructure, there has to be an intermixing of culture, faith, science and technology. We have that kind of living relationship with the river. You [Western societies] have the best technology. So both the societies need to interact with each other to take care of these rivers."

Dr. Mishra was recognized on the United Nations Environmental Program’s Global 500 Roll of Honour in 1992 at Rio, Brazil, and was a TIME Magazine “Hero of the Planet" recipient in 1999.

But rather than claim visionary status, he chooses to raise the standard for all of us: “This is not visionary," he says. “It is simply essential. To aim for less would not be worthy of us as human beings."

To help with the Swatcha Ganga Campaign, or for more information contact:

Telephone: +91(542)313884

FAX: +91(542)314278

Postal address: Tulsi Ghat, Varanasi - 221 005, INDIA

Email General Information:[email protected]t

In Australia:[email protected]

Did you like the article? Subscribe here to our New Article Email Alert or RSS feeds.

Sharing is caring! Don't forget to share the love, and keep the conversation going by leaving a comment below:

Advertisement