One Mouth, Two Hands:

Inside India’s Population Paradox

By Brook & Gaurav Bhagat

“A child is another mouth to feed, but he will have two hands to work and bring in money for the family, especially as the parents grow older," said Mrs. Asha Rane, explaining why it is often the poorest families who have the most children.

The world population in 1930 was about 2 billion; in the year 2000, around 6 billion; and in 2050, according to estimates from the U.N. Commission on Population and Development, it will hit 9 billion. 98 percent of this growth will be in the developing world, where resources are being consumed faster than they can be renewed-- and India will be at the forefront of the crisis.

Rane, who was a professor at the Tata Institute for Social Sciences, now sees the effects of this phenomenon first-hand at the Hamara Club, a project which helps children living on the street in Mumbai. Understanding how and why poverty leads to increasing population is essential to curbing, or at least slowing, the tide.

Currently at 1.24 billion people, India is not far behind China’s 1.34 billion; and, because of China’s well-known government policy of one child per family, its population has stabilized and

is expected to level off soon. According to the U.N., India’s population in 2050 will have overtaken China at around 1.6 billion, to claim the ominous title of the most populous nation on earth.

is expected to level off soon. According to the U.N., India’s population in 2050 will have overtaken China at around 1.6 billion, to claim the ominous title of the most populous nation on earth.

What are the causes? Aside from the aforementioned reasoning of more children helping the family survive, one major factor has been the increased life expectancy in India. In 1947, when India gained independence from British rule, the average life expectancy was only 33 years. Now, thanks to improved standards of living and healthcare, that number is in the mid-60’s.

As life expectancy increased, the birth rate has been falling-- but not fast enough to make up the difference. India was the first country in the world to launch a national family planning program, which has had success. The total fertility rate has declined by more than 40 percent since the 1960’s, and today the average number of children per woman is around three.

The current approach focuses on improving women’s educational, social and economic opportunities-- statistics show that as their status in these realms improves, their family size declines naturally. This positive message is in part an effort to make up for a backlash against the harsher messages of the family planning program in the 70’s. At that time, the government declared a population “state of emergency," which implemented forced sterilizations in the country’s poorest regions and even rewarded medical workers who performed the most operations. This led to a conception, especially among women, that birth control was synonymous with sterilization-- an all-or-nothing decision that they then chose to forgo entirely.

Current aspects of the family planning program include financial incentives for families, and their children’s educations, when they do get sterilized. Birth control pills are incredibly cheap and easy to obtain, especially in comparison to supposedly “developed" nations’ policies-- in India the cheapest brands cost about 8 rupees (appx. $ 0.20) per month at any pharmacy, with no prescription necessary and no questions asked.

Another key issue targeted by Indian public awareness campaigns is favoritism for male children, a value deeply ingrained and interwoven with the cultural structure. Traditionally, when girls get married, they first of all must offer a dowry, and secondly they go to live with and care for their new husband and his parents.

It is not unusual for a poor family to spend their entire life savings on their daughter’s dowry and extravagant wedding (which is also their burden). Then, unless the girl’s parents have a son as well, they are left with no one to take care of them in their old age. Thus the desire for boys drives couples to either keep having children if their first or second children are girls, abort female babies or even commit infanticide.

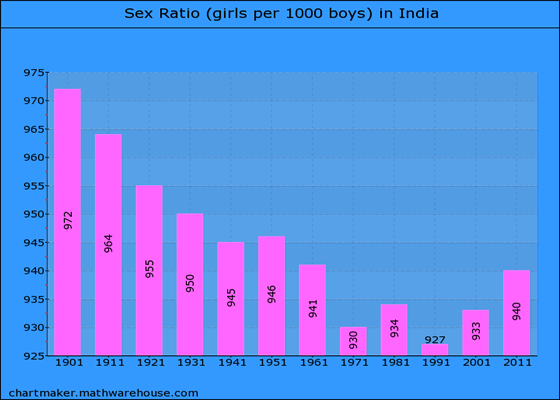

This preference for males has resulted in women being outnumbered by men in India by 32 million, according to the U.N. While the implications of this discrepancy are still largely unknown, it is not likely to benefit women or make them “more valuable," as the law of supply and demand might imply.

Geeta Rao Gupta, president of the Washington, D.C.-based International Center for Research on Women, says that evidence suggests the opposite-- that if the sex ratio imbalance worsens, so will conditions for women. She said that it forces women to marry at a younger age, if less women are available. She also predicts that there will be a greater entrenchment of the dominance of men, because there will be fewer women to speak up, and show that they are valuable. And raising the status of women is essential to lowering the fertility rate.

In ancient India, women enjoyed power and freedom in the family, marketplace, government and even scripture-- for every god in Hinduism there is a goddess. But a thousand years of invasions and occupations by outside forces led to women being secluded in the home, and excluded from community and even family decisions. Superstitions and cultural mores continued to reinforce practices that had lost their usefulness. But outdated thinking has changed widely in urban areas.

“[Birthrates are declining] primarily because of improved access to modern contraception," said Rao Gupta.

“Also because of improvements in women's status globally, and by that I mean improvements in educational status, access to economic opportunities, and a new perception of women's role in society. [Many Indian women] have employment and hold the highest positions in industry and government. Indeed, we've had an Indian prime minister who was a woman.

“Yet the reality is that the majority of young Indian women are very disempowered. They have a much lower status with regard to education and literacy,

with regard to income and economic opportunities, with regard to access to health care and health-care services. Women, especially young women, have very little control over reproductive decision-making for themselves."

with regard to income and economic opportunities, with regard to access to health care and health-care services. Women, especially young women, have very little control over reproductive decision-making for themselves."

Often, especially in poorer, more traditional families in India, the husband’s family has as much or more to say about how many children a couple should have and how fast they should have them than the husband and wife themselves. Since the burden of raising and caring for children is borne primarily by women, Rao Gupta says, given free choice, they almost always will choose smaller families than society will for them.

The status of women, however, has improved and continues to change as India changes-- the economic boom, technological advances, and the increased mobilization of society has altered in many cases the entire family structure. Joined families, a household consisting of parents, their sons and their sons’ wives and children, are becoming less common, and nuclear families are on the rise.

More and more, two incomes are necessary or desired, so women are working outside the home. And, in a nuclear family, although there are certainly disadvantages to this development, the in-laws’ influence, or pressure to have more children, is less than in a joined family. And without grandparents and aunts and uncles in the home to help care for the children, especially if both parents are working, it is simply not feasible to have a large number of children.

India has a quota for women in government-- it is currently 33 percent for local government bodies, and bills have been repeatedly introduced to make that number 50 percent locally and nationally as well, although they have not been passed.

It is now illegal to demand a dowry for marriage (although giving gifts is legal). It is illegal for a doctor or medical worker to reveal the sex of a baby from a sonography report, although it is still done.

Photo: Jeanne Higham

Women’s employment is increasing more quickly than any other group in India, which is key to raising their status. Goverment investment in girls’ education (secondary as well as primary) has also been shown to cause a chain reaction of positive results. An educated woman is statistically more likely to earn an income, have less children and provide those children with better nutrition and health care. This outcome benefits the family, community, and eventually the world.

The numbers, however, are not slowing down fast enough. To support a population of 1.6 billion in 2050, India would have to dramatically increaase agricultural production-- but there is no way to increase the amount of available fresh water, which is already in short demand.

Montek Singh Ahluwali, deputy chairman of India's influential Planning Commission, argues that India can eventually provide such a population.

"Resources at the moment are very sub-optimally used," he said. "I think it's possible to manage that kind of population provided there is a systemic change in how we deal with resources which are becoming scarce. The scope for increased efficiency is very large. That's the nature of the development challenge that India faces."

He may be looking at the glass as half full, but the empty half depends on the increased efficiency of primarily government agencies-- which sounds to many like a contradiction in terms.

It also always seems to be under debate in India to barr individuals with more than 3 or 4 children from entering politics as a public example. This idea, however, has not been put into law, and probably won’t be. The poster child, or rather anti-poster child, for this cause is Lalu Prasad Yadav, a member of Parliament and the Minister of Railways. He has nine children, which he claims is a personal protest against the forced sterilizations of the 1970’s. For those familiar with the economic and population trends in India, it comes as no surprise that Mr. Yadav hails from, and was formerly Chief Minister of, the state of Bihar.

In Bihar, which literally means, “the land where Buddha walked," the average number of children per woman is more than four, and the life expectancy less than 60 years. Contraceptive usage is less than half of the national average, and only 35 percent of women have heard of HIV/AIDS, compared with 57 percent nationally. According to the the National Family Survey of 2006, only 17 percent of the women in Bihar had access to three rounds of antenatal care before their last child was born. What will happen to these little buddhas? For the poorest 20 percent of Indian children, the chances of survival is worse than in Bangladesh or Vietnam.

Yet, in Southern states like Maharastra, income and literacy rates are high and fertility is low-- about 2 children per woman, balancing out the poorer, more rural states to the North like Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan and Bihar and pulling the national average fertility rate down to 3. One of the most essential issues to be addressed is the discrepancy between these different states and regions of India.

According to the United Nations Population Fund’s report on the state of the world population, 2007 was the year that the global urban population outnumbered the rural half of the world for the first time, at 3.3 billion. By 2030, this number is expected to reach almost 5 billion. The urban population of Africa and Asia will double in less than a generation. This unprecedented shift to the cities, large and small, could enhance development, create opportunities and accelerate sustainability-- or it could deepen poverty exponentially, and accelerate environmental degradation.

The outcome will depend largely on the management of the migration by governments, city planners and social agencies-- most of the newcomers will be poor, and demographically young. They often have little choice but to live in city slums, which have higher fertility rates, higher rates of disease due to poor sanitation and water, and higher casualty rates in natural disasters.

It is not necessarily, however, a gloomy prognosis: historically, the urbanization of countries generally leads to development and a higher standard of living, as we see in the Southern states of India. Identifying populations at risk, planning infrastructure and housing policies, orienting furure urban expansion, and generating early-warning indicators about rapidly growing population growth in particular areas are all tools that can help policy-makers manage the changes ahead.

One aspect of urban planning that must not be forgotten in the rush is open space and vegetation. While cities may benefit humans economically, it is important to remember that living in such close quarters with one another, and away from greenery and natural landscapes, is not natural for us.

The hardness, grey color and anonynmity of cities often leads to a loss of a feeling of commumity and friendliness; this contributes to lonliness, depression and to the higher crime and homicide rates in urban areas. The shift to the city is often a move away from extended family members to begin with; migrants find themselves suddenly in a harsh and unfriendly environment.

Public spaces like walkways and parks are often the only leisure the poor can afford to enjoy, and they are crucial to a sense of well-being in cities. Everyone is welcome in open public spaces; they are key to keeping the peace and benefitting the whole.

While the increasing population is a reality that must be planned for and managed, there is a recent theory among economists and the media that India’s booming population is not a problem at all, but a “demographic dividend" that will pay off for everyone.

Many developed nations’ birth rates have stabilized, and some are even negative, like Japan and Italy. They are increasingly facing a greying of their workforces, and will have shortages of workers in the future. Even China’s stabilazation will ultimately result in a workforce crunch within 25-30 years, as the current workers grow older. Only India is projected to still be a “young" country at that time, with the majority of its population in the working age. So, the logic goes, India will be in a position to both attract jobs and export workers to the “old" countries.

While the theory certainly has some truth to it, the demographic dividend that is earned will not amount to much when the human and environmental cost of such a large population is taken into consideration. The population issue has been pushed so hard by the Indian government for so long that it feels refreshing, especially to the media, to hear that there might be a flip side to it. Imagine being nagged for years that smoking is bad for your health. If you find an article that says it might increase hand-eye coordination, you might make a copy for everyone you know. But that won’t stop you from getting cancer.

While other countries may export jobs, they are not likely to export water, land, clean air or forests. If there are some positive side effects to India’s booming population, that’s great. But that doesn’t make the disease any less deadly. We have to keep nagging, keep trying to shake each other awake. Because in the end, while some suits may reap a dividend, it is the children who will pay the price.

Did you like the article? Subscribe here to our New Article Email Alert or RSS feeds.

Sharing is caring! Don't forget to share the love, and keep the conversation going by leaving a comment below:

Advertisement